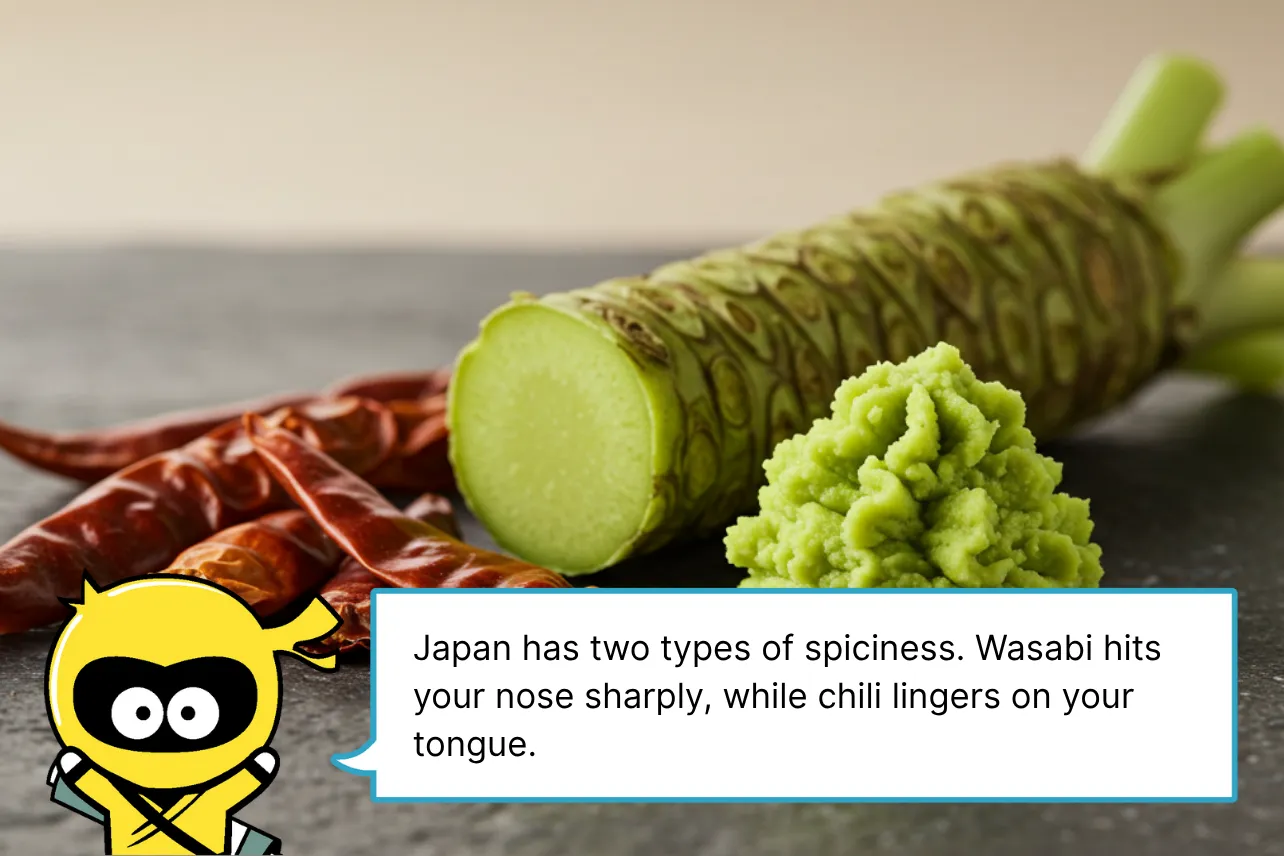

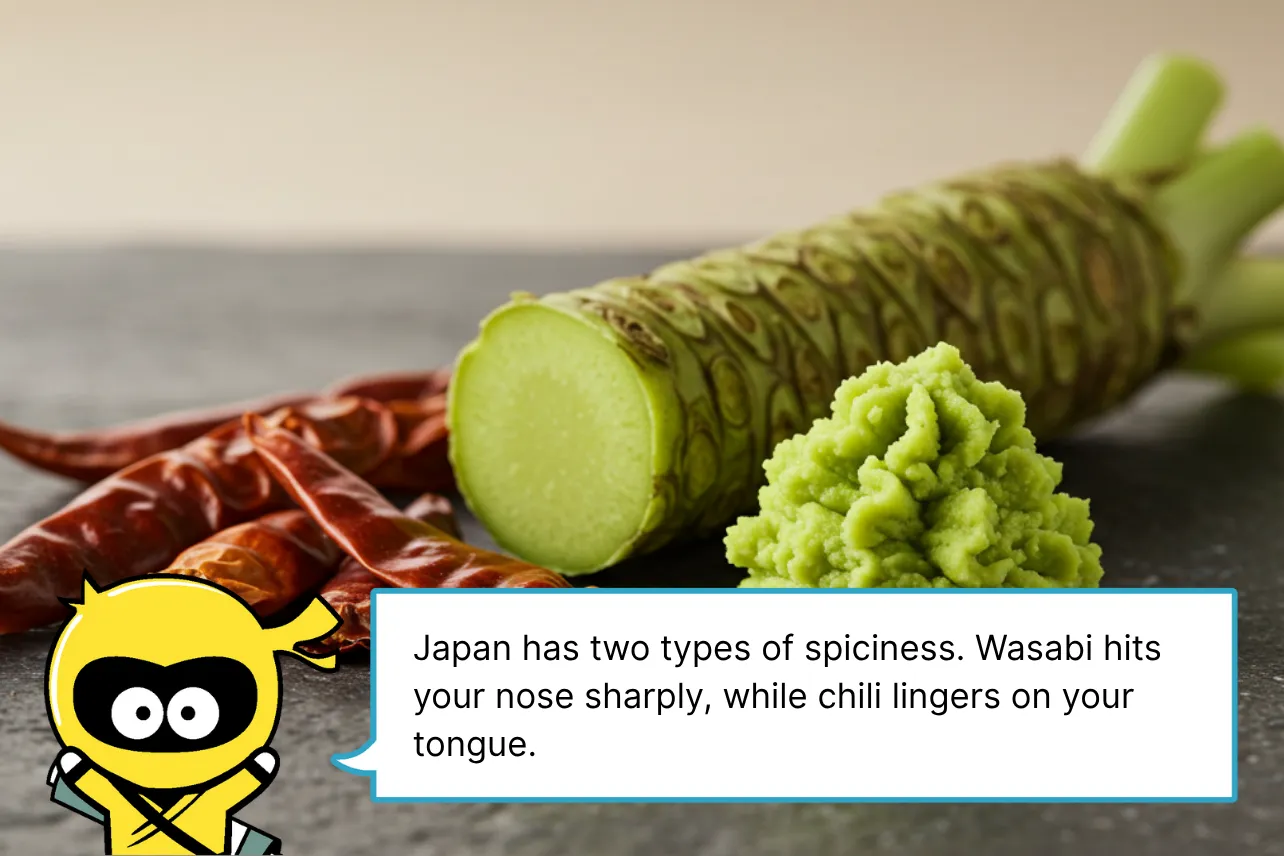

One of the biggest surprises for foreign travelers dining in Japan is how different “spice” feels. A bite of wasabi with sushi can bring tears as the sharp heat rushes through your nose, while a bowl of chili-spiced ramen leaves you reaching for water. Though both are “spicy,” Japan offers two very different flavor experiences.

Many visitors wonder: “How is wasabi different from chili peppers?” or “Why does Japanese wasabi taste so unlike the chili heat I know?”

In this guide, we’ll explain the key differences between wasabi and chili so you can enjoy Japan’s spicy food safely. From the science behind the flavors to cultural meaning, proper dining etiquette, and unique food experiences at tourist spots—you’ll discover how Japan’s unique spice can become a memorable part of your trip.

Wasabi vs Chili in Japan: A Complete Guide to Unique Spicy Flavors

The first shock for many travelers in Japan is realizing how differently wasabi and chili deliver heat. Wasabi on sushi creates an instant, sharp sensation that rushes through the nose but quickly fades away. Chili peppers in ramen or curry, on the other hand, leave a lingering burn on the tongue, often making you sweat as you continue eating.

Tourists often share comments like: “Wasabi made my eyes water but I got used to it quickly,” or “The chili heat kept building and was far stronger than I expected.” Both are spicy, but the physical sensations are completely different—so newcomers should be cautious. Misjudging the spice can make it harder to fully enjoy your meal.

In Japanese dining culture, the two are used strategically. Wasabi enhances the freshness of raw fish, while chili peppers warm the body and flavor hearty dishes. For visitors, experiencing both types of spice isn’t just about food—it becomes a travel memory. With the right knowledge, you can safely enjoy recommended dishes without worry.

Why Does Wasabi Burn the Nose? Easy Science Explained

For many first-time sushi eaters, the most shocking part is wasabi’s sharp, nose-clearing heat. Unlike chili, which irritates the tongue, wasabi produces a quick, piercing sensation that often brings tears. This comes from allyl isothiocyanate, a volatile compound that directly stimulates the nose and throat membranes.

Travelers describe it as: “So strong with just a little, but gone in seconds,” or “Less scary than chili, but a strange and unforgettable experience.” Because the spiciness doesn’t linger, many find it less overwhelming—but adding too much ruins the flavor balance. At sushi restaurants, simply request “without wasabi” if you’re sensitive.

Knowing the science makes the experience less intimidating. Wasabi also has antibacterial benefits, which is why it’s been part of Japanese cuisine for centuries. Some tourist farms in Nagano or Shizuoka even offer fresh wasabi tasting tours. The cost ranges from a few hundred yen to several thousand, but it’s a unique souvenir experience worth trying.

Chili Heat in Japan: Scoville Scale and Spicy Food Tips

Chili peppers bring a very different type of heat compared to wasabi. The lingering burn comes from capsaicin, measured in “Scoville units.” Common Japanese chili powders like shichimi have moderate levels, but specialty spicy ramen can reach extreme heat, a completely different experience from wasabi.

Capsaicin dissolves in fat, not water—so if your mouth burns too much, milk or yogurt is far more effective than water. This simple tip helps travelers enjoy spicy Japanese food without discomfort.

You might be interested in this

Proper Way to Use Wasabi with Sushi and Soba

Many visitors are unsure how to handle wasabi in traditional Japanese meals. For sushi, chefs usually add the correct amount themselves, so piling on extra wasabi isn’t necessary—and often spoils the balance. If you prefer less heat, politely ask for “no wasabi” (sabi-nuki).

With soba noodles, the custom is not to stir all the wasabi into the dipping sauce. Instead, place a little on the noodles with your chopsticks and dip lightly. Learning this etiquette makes the meal more authentic and helps you better understand Japanese dining culture.

Real Wasabi vs Powdered Wasabi: Where to Try the Authentic Flavor

Not all wasabi served in Japan is the same. True wasabi is a luxury crop grown in regions like Nagano and Shizuoka, freshly grated with a mild aroma and refined heat. Powdered wasabi, however, is usually made from horseradish and mustard powder, cheaper and common in conveyor-belt sushi or supermarkets.

To taste the real thing, wasabi farms are a great travel experience. In places like Azumino or Izu, you can tour wasabi fields and grate fresh wasabi yourself. Entry fees range from a few hundred to a few thousand yen, but it’s a rare food adventure. Local specialties like wasabi ice cream are also popular among tourists.

Keep in mind: authentic wasabi is delicate, so if you buy it as a souvenir, you’ll need to store it carefully. High-end sushi restaurants often use real wasabi—the price may be higher, but the taste is unforgettable. Knowing this difference makes your food experience richer and your trip more memorable.

Unique Travel Experiences: Wasabi Ice Cream and Chili Snacks

Among the most fun food experiences in Japan are quirky spicy treats. In Nagano, Shizuoka, and highway rest stops, wasabi ice cream is a must-try. It looks like normal soft serve, but the sweet cream is followed by a surprising wasabi kick. Tourists often say, “Strange but delicious,” or “The mix of sweet and spicy was unforgettable.”

Spicy souvenirs like shichimi rice crackers or extra-hot chili chips are also easy to find and affordable, usually just a few hundred yen. These unique snacks make perfect gifts and let travelers sample Japanese spice outside restaurants. Sharing such unusual finds on social media has become part of the adventure.

These small but memorable experiences enrich your Japan trip. From wasabi sweets to chili snacks, tasting both sides of Japan’s spice culture adds flavor to your travel story.